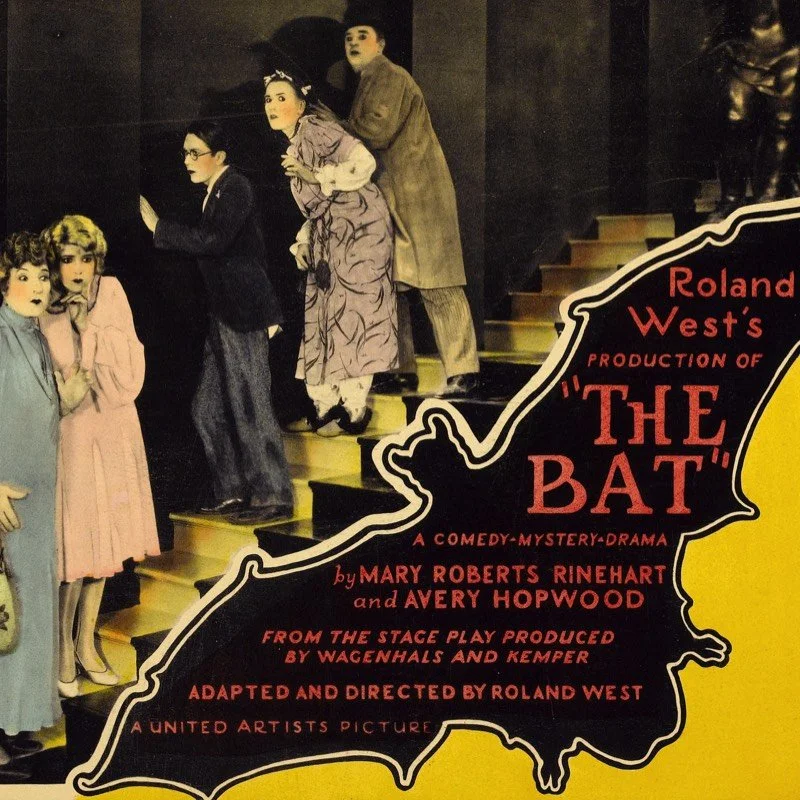

Batty ‘bout THE BAT (1926 movie)

THE BAT (1926)

I watched (or rather re-watched, in 2 out of 3 cases) the film versions of The Bat in reverse order, starting with the 1959 production, then the 1930 widescreen talkie, and finally the 1926 silent version.

I’m glad I did.

Save the best for the last.

Between the stage and first screen version of the story, a novelization was published (purportedly by Mary Roberts Rinehart and Avery Hopwood themselves but actually ghost written by Stephen Vincent Benet), and one can see somebody early on gave serious thought on how to adapt a very stage bound story into a motion picture.

Both the novelization and the movie open with The Bat committing murder and jewel theft, then taunting the police by leaving a note telling them he’s heading off to the country for a vacation.

Once in the country, the story follows the basic plot of the stage play with a few exceptions, some minor, some medium, none really altering the story.

The police detective is now Moletti, not Anderson; Anderson becomes a comic relief private eye who wanders the premises brandishing two large revolvers (at one point in the proceedings there are five different guns being handed about). The butler is no longer the mildly offensive stereotypical Washington but the holy-mother-of-pearl-wot-da-hell-were-you-thinking Japanese man servant Billy [sic!] who is made up to look like one of the aliens from The Outer Limits.*

The Bat hizzownsef is seen rather than talked about as he is in the stage play, and that’s what makes this version stand out over all the others.

They also reduce the amount of cash stolen from $1,000,000 to $200,000 because somebody figured out even in hundred dollar bills a cool million is a lot of moola to lug around.

There’s a saying in show biz that nobody leaves the theater humming the scenery.

The 1926 version of The Bat is the exception to that.

The film was designed by William Cameron Menzies, a production designer / art director / screenwriter / producer / film director with an astonishing resume: The Douglas Fairbanks and Michael Powell versions of The Thief Of Bagdad, Chandu The Magician, Alice In Wonderland, Things To Come, Nothing Sacred, The Adventures Of Tom Sawyer, Gone With The Wind, Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Spellbound, It’s A Wonderful Life, Invaders From Mars, and Around The World In 80 Days -- and that’s only a quarter of what he did!

Mary Pickford (older sister of Jack Pickford, who plays Brooks Baily in this version) once observed that it was a pity movies learned how to talk; they would have been so much better if they evolved the other way around.

The Bat is a perfect example of what she meant.

Menzies gives the film a literally larger than life, unreal dream-like quality. Miniature shots depicting the mansion and the bank and the skyscraper where The Bat commits his first crime of the film deliberately look toy-like.

This is not inadequacy on Menzies’ part but a deliberate artistic choice.

The Bat also flies, something he does in no other version of the story, and his costume makes him look less like Batman, more like something out of a Mexican horror movie.

And the sets -- yowza!

The sets are huge, beyond palatial, representing a size and scope that dwarf the story going on. This overwhelming art direction doesn’t lose the plot, it ignores it completely.

The Bat under Menzies’ art direction becomes a dream-like construct, more so than his overt fantasies ever were.

This air of unreality works in the film’s favor; we lose interest in the mechanics of the plot and simply follow the story as it rushes along at a headlong pace.

There’s nothing in the slightest that’s realistic about this version of The Bat and to that I say thank you. (Decades later Menzies revisited this style of set design with Invaders From Mars a prolonged dream sequence presented as a sci-fi story, with the sets becoming more and more stylized as the film progresses.)

The only way to improve this film would be to jettison the intrusive intertitles, used too often an attempt to work stage dialog into the story in a vain (and foolish!) attempt to fill spaces best left silent.

The Bat was directed by Roland West, who certainly kept things moving at a frantic pace. West was a respected film director at the time and seemed poised for a long, successful career but The Bat Whispers, his 1930 sound remake of The Bat proved his next to last film.

West became one of those people whose lives, seemingly blessed and fortunate, suddenly start unraveling at incredible speed. Implicated in the death of his mistress, actress Thelma Todd, he vanished from the Hollywood scene, becoming reclusive and ironically remotely involved in one of the great real life sea mysteries of the Pacific.

The success of both the stage play and screen versions of The Bat led to numerous imitations, including The Monster (1925, starring Lon Chaney and also directed by West), several versions of The Cat And The Canary, The Old Dark House (1932; remade in name only in 1963), plus lord knows how many B-movie and serial knock offs. While the genre pretty much ran out of steam by the late 1930s, it still cropped up occasionally in various Abbott & Costello movies, the animated TV series Scooby Doo, Where Are You?, and of course, The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Long considered a lost film known only by a handful of stills featuring Menzies’ impressive sets and bizarre Bat costume, The Bat was rediscovered and restored in the 1980s and is widely available today.

(If I were king of the forest and had a time machine, I’d see to it that Harold Lloyd was cast as Brooks Baily the accused bank clerk turned gardener, Lon Chaney as Detective Moletti / The Bat, Margaret Dumont as Cornelia Van Gorder, and Laurel & Hardy split the role of private eye Anderson.)

© Buzz Dixon

* Since posting this I’ve learned the character of Washington was added to replace the original Japanese house servant during the WWII revival of the play, and that all filmed or broadcast versions adhere to the original, at least so far as the character’s name, Billy (yeah, that sounds really Japanese…).

![Time Travel [FICTOID]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/590697e7d1758ec4d7669624/1594606276161-MU9I5ZCNHBL1KJISZ08J/FT+103+Time+Travel+-+Ed+Emshwiller+-+SQR.jpg)